Introduction to Net Contribution

Table of Contents

What is net contribution?

How did we get here?

Why is the net contribution mindset important to Heron?

What is our net contribution lens?

What principles guide our net contribution lens?

How does Heron apply the net contribution lens to our work?

In good company as we look to the future

What is net contribution?

“Net contribution” is the aggregate effect of an enterprise on the world. Enterprises include for-profits, nonprofits, and government enterprises, and they can affect their communities in a variety of ways — some positive (like hiring people and paying taxes), and some negative (like polluting local rivers and exploiting local workers).

We ask whether, on net, the world is better off with or without any given enterprise based on its net contribution to people, place, and planet.

The concept of net contribution is designed to be flexible, translatable, and customizable. We ask investors to think about the net contribution of their investments, companies to think about the net contribution of their activities, and community leaders to think about the net contribution of local enterprises.

How did we get here?

Over the years, Heron has pursued our mission through a variety of strategies, but the desire to invest in businesses that support a thriving society was always in our DNA. In 2011, even as Heron’s strategy was shifting to a focus on jobs, board chair Buzz Schmidt wrote in Nonprofit Quarterly of the need to better understand enterprises’ overall positive and negative impacts on society’s wherewithal, and implored investors “to take full and conscious responsibility” for investing in those with a positive net impact:

At the end of the day, we don’t need more analysis documenting the exploitative qualities of commercial enterprise nor a new corporate epiphany about their potential to build lasting societal value. There are already thousands of truly great wherewithal-creating commercial enterprises out there. These are enterprises that build a globally competitive work force; enhance the quality of civic life and opportunity for citizens; strengthen our economic, physical infrastructure and political systems (and, just as importantly, public faith in those same systems); generate our store of intellectual property; impact neutrally or positively the quality of our climate and natural environment; and generate long-term financial wealth.

Likewise there are companies that through their policies corrupt our political and financial systems; erode public faith in the fairness of economy; market products that seriously diminish the health and welfare of the population; and rip communities apart, generally dissipating society’s wherewithal, despite “healthy” reported earnings.

In the final analysis, how an enterprise operates is fully as important for our productive future as what it produces or what it earns. For society’s purposes, the so-called externalities that result largely from the “hows” of enterprises doing business are intrinsic, inseverable components of their core activity. Before we spend any more time building new corporate forms and collaborative constructions, we must recognize the vast differences in the net contributions these enterprises make to society’s wherewithal and put our money where our values are. This recognition is especially critical in an era in which everyone understands the limitations of government. We can no longer cavalierly ignore the net positive or negative contributions that our enterprises make to society’s wherewithal…

In this podcast, Dana K. Bezerra, former president of the Heron Foundation, discusses why assessing the aggregate effect of an enterprise matters for impact measurement.

Heron’s “portfolio examination project“… was our attempt to… approach this investing 100% for impact [by understanding] what we already owned. As we started looking though the underlying positions, back to this notion of trade-offs, sometimes things looked really good until you got additional data, and then they didn’t.

This nascent language started to emerge, honestly a little bit out of frustration, around, “Great. That’s a great data point, but on net would we choose to own this company? Or on net would we choose to make this investment?” And in part that language evolved into this net contribution framework, where we tried to look really across the aggregate effect of an enterprise. So if you have a business doing what it does, we’re not going to isolate and look at jobs. We’re not going to just look at products and services, but try to ask the question across the totality of what an enterprise does, from employing people to potentially polluting or creating a product and service that may or may not be a great health outcome for example, would we want to own the company?

“We had a lot of naïve assumptions over time that fell by the wayside… we thought the framework would help us have answers, and what we’ve learned is that the framework just really helps us ask better questions.”

Dana K. Bezerra

Why is a “net contribution” lens important to Heron?

Stubbing Our Toe on Corrections Corporation of America

In 2011, Heron committed to putting all of our capital to work for our mission. We started by examining what we already owned, with a specific focus on jobs that could help lift people from poverty. What we found was not always what we expected, as when a job-laden real estate investment trust turned out to be Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the biggest private prison operator in the United States.

The private prison business model raises major concerns on a number of social, governance, and even environmental fronts. Heron also found that while CCA (now CoreCivic) did in fact employ thousands of people, their SEC filings did not specify how many prisoners were also doing work, what kind of pay they were receiving (if any), whether that work was within the prison system (e.g. cooks, janitorial staff) or for outside companies, and other information key to the business model from an investment perspective. (On looking further, we found that many Americans unwittingly owned private prisons through their pensions and 401(k) plans.)

Based on those risks, both social and financial, Heron decided to divest from CCA and began organically thinking about the overall impact of enterprises rather than just their jobs. Being focused too narrowly on the number of jobs provided would have led us to miss the larger impact of these enterprises on the people and communities about whom we care. In addition, we didn’t want to simply screen out all private prisons, just as we don’t screen out any industry in its entirety. Rather, our goal is to continuously improve the data informing our investment choices, so that Heron will be better positioned to optimize the portfolio for social and financial performance.

Evaluation of Residential Property

Another more recent example started when we became aware of the potential social costs of a green-energy investment known as Property-Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) Bonds. PACE Bonds are attractive to environmentally conscious investors for both their contribution to energy retrofitting and their low-risk financial returns. However, of all the winners in this generally compelling investment, one stakeholder in residential PACE bonds — the homeowners — bear a disproportionate degree of risk:

The current sales practices bypass traditional underwriting procedures such as calculating debt-to-income assessments and similar ability-to-pay ratios. Skipping these investigations can lead to a big jump in the cost of homeownership—and potentially to the loss of the home.

For Heron, this again underscored the importance of looking not only at the intended impact — greener buildings — but at the outcomes for all stakeholders. While we don’t expect that any enterprise will be perfect, or have wonderful outcomes for every stakeholder, we also couldn’t in good conscience invest in a product where risk fell so disproportionately on a single stakeholder.

What is our net contribution lens?

We use the net contribution lens to analyze the way in which enterprises consume and generate different types of capital: human capital, natural capital, civic capital and financial capital.

Human Capital comprises an enterprise’s interactions with individual people with whom they have a direct relationship, including but not limited to their employees.

Natural Capital includes how an enterprise makes use of resources such as energy and raw materials, how they handle waste products, and their effects on the natural environment.

Civic Capital looks at an enterprise’s interactions with communities, including customers, neighbors, and governmental actors such as regulators. One such interaction might be how a company approaches their taxes. (Frequently there is a slight zone-of-control difference between human capital-related behaviors, in which the enterprise has direct and personal effects on individual people, and civic capital, in which there is a slightly less direct level of control.)

Financial Capital looks at an enterprise’s interactions with the economic and financial landscape in which they operate, including most directly their effects on capital providers through governance practices and capital outlay decisions.

What principles guide our net contribution lens?

Heron aspires to apply the following principles as we try to determine the net contribution or detraction of any given enterprise.

Collect and report data at the enterprise level. At Heron, we see enterprises as the unit of impact because enterprises employ people, use or abuse natural resources, serve community needs through their products and services, cause pollution, and otherwise affect their communities (for better and worse).

Measure both negative and positive performance of the enterprise. Enterprises can have positive and negative impacts in different areas and on different stakeholders.

Track and report data over time. Because actions speak louder than words, we attempt to look at historical performance as well as forward-looking promises & pledges. We also recognize that social performance, like financial performance, can go up and down over time.

Track and report data across the totality of the enterprise as it relates to all relevant stakeholders and capitals. Many frameworks look solely at a supply chain, or core operations, or products and services. All of these should be included in the overall analysis of an enterprise’s net contribution. One reason Heron looks at four types of capital, rather than just listing specific stakeholders, is to help us avoid blind spots when there’s a stakeholder involved that falls outside of the usual categories.

Recognize that enterprises have a limited zone of control. An enterprise has varying degrees of control over both the behavior of various stakeholders and the outcomes they experience. We want to hold enterprises accountable for how they use their influence, without blaming them for factors beyond their control.

Whenever possible, ensure that the data has integrity (and is ideally even audited). Different types of data sets carry different sets of risks to integrity. Enterprises are incentivized to present themselves in the best possible light and to avoid excess transparency; third parties don’t always have full transparency; proxies may not always translate well to realities; and many data sets have null responses. Finding and applying data with integrity can be a genuine challenge, but is important to take on with persistence and good faith.

Apply the framework as appropriate across enterprise types, tax statuses, and asset classes. Larger corporations have the capacity to do and report on much more socially positive activity than smaller ones, and also enjoy a greater zone of control. We don’t desire to punish small business for their limited resources or inappropriately hinder early stage businesses. But we do want to encourage all enterprises to contribute more than they consume.

Apply the framework as appropriate on a peer-relative basis. Peers may be defined by size, sector, geography, and/or stage.

How does Heron apply the net contribution lens to our work?

Like many other practitioners, Heron searched for a simple, inexpensive, and intellectually honest way to monitor the social performance of our portfolio. We worked with a variety of data partners to do so, including CSRHub, B Lab, HIP Investor and Oekom.

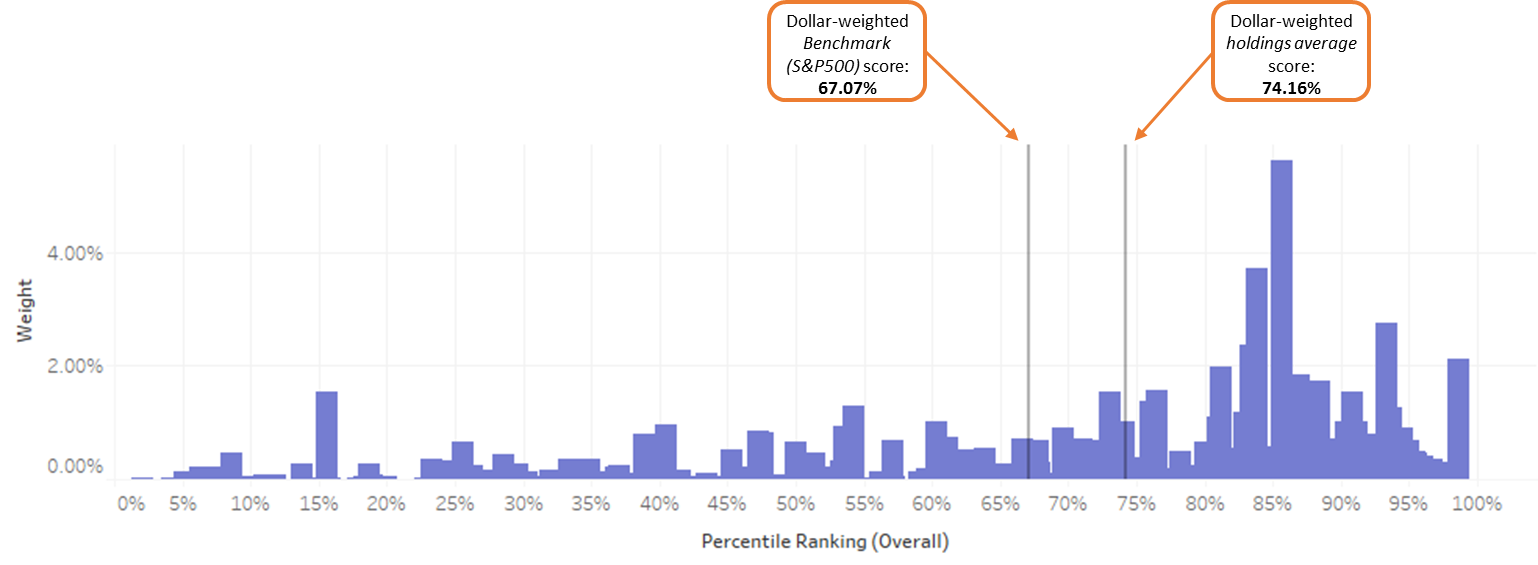

Heron used this data to track the social performance of each company in our portfolio. As an example, the below histogram represents the enterprises that, at the time, was held in one of our impact-screened public equities holdings as scored by CSRHub. The gray line indicates the dollar-weighted average social score of 73.5 percent. The enterprises at the far left of the graph represent a learning opportunity for us: How did they make it through our carefully-designed screen but end up ranked so poorly by CSRHub? It could represent differences in data reported, a time lag, the weighting of different values, or any of a wide variety of contributing factors.

What we learn from the histogram data helped us to identify outliers, monitor trends, and better understand the data available from each company. We continued to work with our data partners, managers, and others to learn from and improve this process.

The lessons learned along the way informed the creation of the The U.S. Community Investing IndexTM (“USCII” or “the Index”; Bloomberg Ticker: CMTYIDX), an index of publicly traded companies designed to identify those that contribute positively to the communities in which they source, operate, and sell. Heron developed the index in 2005 to understand how large companies contribute to (or detract from) Heron’s mission to help people and communities help themselves.

In good company as we look to the future

While we at Heron found it helpful to begin our efforts toward designing a net contribution lens with a “blue sky” approach, we are not the only ones attempting to look at the net effect of an enterprise. We applaud our colleagues in the space for helping push this line of thinking forward.

For our part, going forward, Heron seeks to better incorporate the net contribution framework into our analysis of prospective opportunities and reporting a more complete picture of the net return of a given investment–across all capitals, not just financial.